In light of recent changes to Google Chrome, many forums have filled with bitter discussions. Here are just a few:

- Chrome 69 will keep Google Cookies when you tell it to delete all cookies

- Why I’m done with Chrome (HN discussion)

- Using Gmail? You will be force logged into Chrome

At some point someone inevitably says:

For Google, you are not the consumer. You are the product.

But companies usually care about their products, protect them, try to improve their state.

If I were a product, Google would do its best not to destroy me. They have invested a lot of resources into this product, so why risk it by making baffling changes to both privacy and user experience? If I stay happy with Google’s offerings, I keep being the perfect product: I can be mined for data and “sold” perpetually.

Clearly, Google doesn’t care about me personally. And how could it? There are billions of people just like me who use their services every day.

Maybe we should stop thinking we’re “Google’s product” and start thinking we are data points in endless experiments.

You’re Data Point

What does it mean to be a data point?

- Your personal issues don’t matter.

- You, alone, are not valuable.

- You can be easily replaced.

While this is a gloomy oversimplification, I believe it’s important to recognize the general idea.

You’re playing a role in some “user story”

When you pretend you’re the consumer, you think in terms of goods and services, and a simple two-way relationship. This leads to disappointment every time a breaking change comes in or a service shuts down altogether.

In reality, you are playing roles in many “user stories” and experiments, without knowing it and without knowing what those roles actually constitute.

Figure 1: Product manager’s bedtime user story.

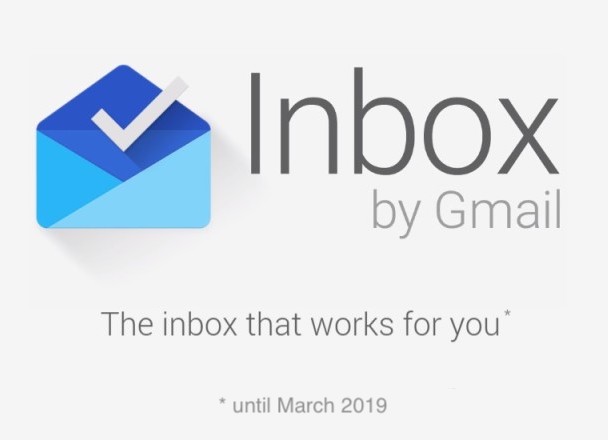

Few weeks ago Google announced that Inbox will be closed next Spring. Many ask the heavens “Why would Google kill Inbox?! I’ve been using it every day and all my friends have!”

I bet it was a successful experiment for Google: by using the app, you’ve generated a lot of important information, helped them learn useful patterns and god knows what else. They are not killing it because it failed as a consumer product, it was never intended to be one. They are not killing it because not enough people used it, or used not extensively enough. Quite the opposite.

They are not really “killing” a product, they are finishing up an experiment.

Just like scientists don’t “kill” good experiments, even though the mice might ask the heavens “why would they kill this maze?! I’ve been running in it every day and all my friends have!”

Figure 2: Google shuts down another product.

Of course, not all Google’s products are experiments. This isn’t a binary thing though: some products are clearly (in hindsight) temporary experiments, some are core things that rarely change, but the majority of apps and services are somewhere between. And you never know what games are you in.

You are punished for being a good data point

If you truly use Google’s products extensively, you are statistically more likely to be punished for that. For example, if you haven’t willingly participated in the experiment called “Google Inbox” and just ignored their promotion, its shutdown won’t affect you negatively. Actually, it will affect you positively: the results of this experiment will help improve the feature set of Gmail, the service you’re probably using.

But if you were a good data point1, and invested a lot into Inbox’ features, you’ll receive a punishment. Your workflow — and an important one! — will just be disregarded.

“We will incorporate many features of Inbox into Gmail” is a weak consolation when in one day your whole email experience just shuts down.

We have to understand this fundamental change of the relationship between companies and users. The main focus for tech giants is growth, which requires data, which requires experiments. The more we participate in data points generation, the more likely we’ll be burned.

Compare this to the old and straightforward concept of “product X is popular, therefore product X will be kept on the market”.

But why? Don’t they want to have popular products? Well, yes, but…

Your personal metrics aren’t aligned with theirs

We might think that “popular is good”, but for Google often “more data points is good”, because that’s the real resource that allows them to grow. Ten different products, launched and shut down sequentially, is a better source of data points than one, long-lived and stable service.

We do not and cannot know what is important in any given experiment. Heck, we can’t even know the scopes and the limits of them. That’s the point of having experiments!

But one thing is certain: our values and metrics rarely align with theirs. Because, as a user, I don’t really care about company’s growth.

You might say “Yeah, obviously! Their goal is profit, nothing new here!”. But it’s different this time. All businesses’ end goal is profit, that’s capitalism, nothing wrong with that. The problem is in the hidden, implicit nature of the relationship. We don’t really know the deal! What can we do? What can we be sure of? What are our rights? What are their responsibilities?

What exactly is the deal?!

You’re a renewable source

Google itself uses your data to grow, but it also uses it for to make money by targeting ads. That’s what people mean when they say “Google sells your data!” and that’s where “you’re the product” rhetoric comes from.

But it’s not like Adidas wants my data. Or yours. They want a large group that satisfies certain parameters.

Figure 3: A company sells your data.

Of course, companies don’t get a .zip-file with names and addresses. They receive the ability to show certain ads to certain people. Google doesn’t sell your data, they sell access to your eyes and ears. So, you’re not just a product, you’re renewable source of products. Your tastes and needs change over time, you can be targeted over and over.

This denies any sort of hope one might have about companies caring about their products. They do, just not about individual items or individual producers. Apple doesn’t care about any particular iPhone device or any particular worker at their Chinese factory.

But I pay them money!

The third aspect is “Google and paid services”. Google sells a lot of things directly, and this must be a “consumer-producer” scenario, right?

Yeah, no.

Google recently increased the fees for Google Maps API about 1400%. This kind of increase means one of the two:

- Previous pricing model was inaccurate.

- New pricing model is inaccurate.

Were they losing money before to conquer the market? Or did they just decide to make a buttload of cash using the conquered market? Either way, the problem is the same: we had no idea what the deal is.

Another example is Google Cloud, a platform used by many large businesses. You can lose everything in 3 days and deal with a pretty bad support even though you’re paying client.

Not to mention the lack of visibility in changes - it seems like everything is constantly running at multiple versions that can change suddenly with no notice, and if that breaks your use case they don’t really seem to know or care. It feels like there’s miles of difference between the SRE book and how their cloud teams operate in practice. (comment in a relevant discussion)

Are they underfunded? Is their goal to make a reliable platform or is it something else? What do they take into account when they make changes? We have no idea.

This is not just Google

It’s easier to talk about Google because they seem to be the biggest company in this area (or ever). But this is the reality for a lot of businesses, not necessarily in the advertisement industry.

Once the company is large enough, all customers become data points. This is okay in principle. I can live with that, as long as I understand it. This is a question of honesty.

If Google said upfront:

We’re launching this new product X, but it’s an experiment. We’ll work on it for at least 5 years, but can’t guarantee anything after that. We might shut it down with short notice. Would you like to participate?

Then there would be no point in complaining. That’s a fair deal. Of course, this kind of frankness wouldn’t help Google. It’s like telling the participants of a sociological experiment about all details of said experiment. It poisons the data. Scientists want unsullied results.

Figure 4: I hope I’m not sued for this…

If Google said upfront:

We’re giving you a lot of awesome products free of charge. But we’ll collect as much information on you as possible, and if we’ll keep changing the services and terms to collect more data. We will use this information to target ads and maybe do something else. Would you like to participate?

That’s a fair deal too. You are free to give up anything, as long as you understand what’s going on. Of course, this kind of message doesn’t survive the path from Terms of Service to The Marketing Department.

But you always read ToS, right?

All that is obvious in hindsight (in those forums, there’s always at least one guy who says “what did you expect?”), but we have to learn to infer these things from the business models. This is not our jobs, but that’s the reality. We have to understand all the implications of these new, weird businesses.

Every time you see a new startup, new app, new service with some interesting features, and it’s clearly not a simple “I pay, you provide” kind of deal, beware. What are the implications?

Conclusions

Let’s summarize:

- Growth, not simple profit generation is the main focus.

- Growth requires data. Experiments, changes and seemingly weird decisions generate data.

- For Google and many tech giants, you are a data point.

And as the result:

- We no longer interact with businesses. We interact with the top layer interface of a multi-layered, non-obvious system built with implicit, vague rules.

- Never before were users’ and companies’ goals so irrelated to each other.

- We’re constantly playing games we’re not aware of.

- We have to learn to understand the implications of this.

Final words

Not all is bad. This symbiosis can be very benificial for all parties. We can explicitly play roles of consumers, products and data points at the same time, knowing what’s happening and being in control. Companies can play whatever games they need to play with us.

Extremely relevant ads and extremely personalized user experiences sound pretty good to me, all the creepiness aside.

Legislation will never catch up in time, so we have to take things into our own hands and learn to live in this brave new world.

Rather, a generator of myriads of data points, but “data point” sounds more inhumane and humiliating, so I’ll stick to this term for dramatic purposes. ↩︎